Like many Black women, my hair story began as a little girl subject to hair care and styles determined by my mother. I have memories of my hair in plaits and ponytails with noisy hair ties and barrettes; and can see and smell the grease used to smooth and brush my hair into those styles. I remember my mom straightening my hair with a hot comb, heating the comb on the kitchen stove, and telling me to sit still and hold my ear. I can hear the sizzle of heat meeting grease and feel the hot, metal comb getting just a little too close for comfort. Eventually, I progressed to a rite of passage for many Black girls: transitioning from the kitchen and sitting on the floor between my mother’s knees to regular appointments at Ms. Jean’s beauty salon.

I didn’t get a relaxer until high school and, when I did, I wanted bone-straight hair. For years my mom, a cosmetologist who had recently transitioned from short, relaxed hair to a mini afro, encouraged me to go natural. She insisted I wear my hair as it grows from my head, which is in very tightly coiled curls. My answer was always a resounding (but respectful) “No.” I placed such value on straight hair as a primary component of my aesthetic appeal that I failed to see any benefit in going without a relaxer. I literally couldn’t picture my own, unique curl pattern, nor envision the beauty in it. In 2011, one bad relaxer changed the game. I could smell the fried hair with every turn of my head. When I saw my mom, she confirmed in her matter-of-fact way: “You gotta cut it all off.” I have no doubt she was giddy inside.

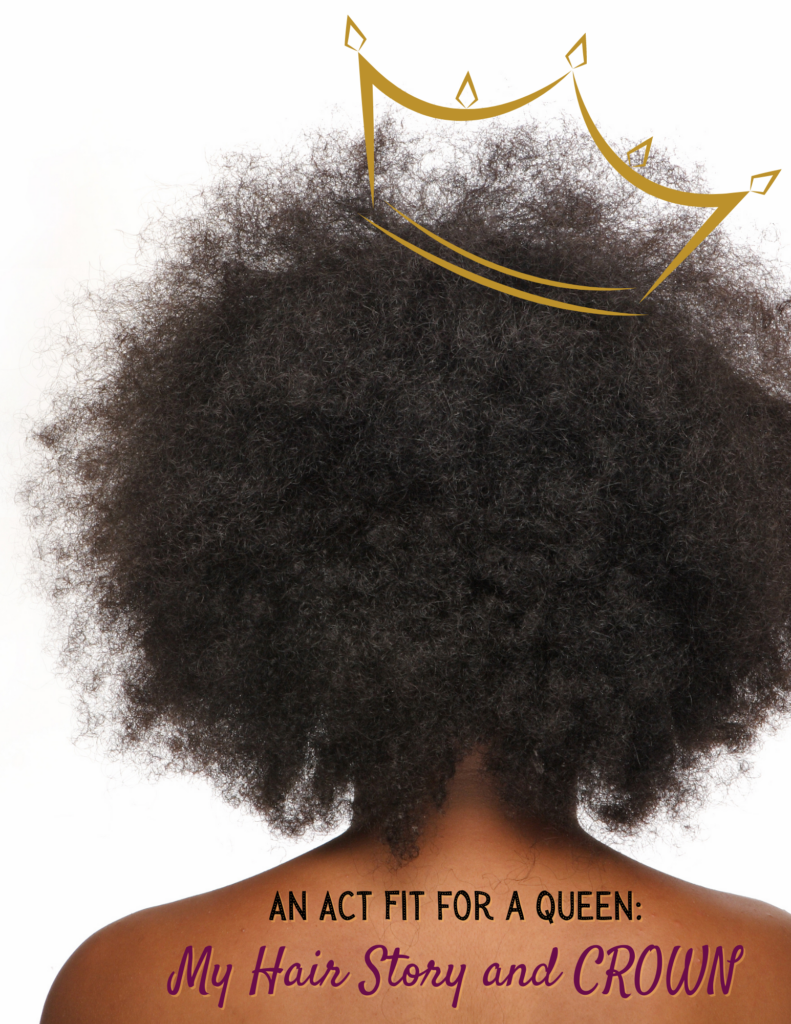

So, I (we) did the big chop. With less than an inch of hair remaining, I felt free but had reservations about my partner’s response and co-worker feedback. While I didn’t need my partner’s approval, I cared about his opinion. Thankfully, he was affirming and supportive. At work, I received my first negative reactions from the Black, male security guards. Shocked by my new look, they didn’t try to hide their disappointment and were vocal about their disdain. Black women questioned the appropriateness of my hair or admitted they were scared to do the same.

What some consider a simple hairstyle change affected me enough to rethink my dissertation topic. I considered how younger, Black women might experience projection of unsolicited opinions, advice, and perspectives rooted in historical context dating back to slavery; and attempts to conform to American beauty standards, while simultaneously staying true to themselves. This is Black body politics: the constant navigation of social and systemic barriers to our physical being, an imposed balancing act stemming from the desire of those in power to remain in power.

White slave traders knew African men and women’s hair was inextricably linked to identity, with hair used as a means of communication, an indicator of social status, and form of identification. Various styles, lengths, and textures belonged to particular tribes or were associated with specific geographic locations. The unifying thread was hair’s social and cultural significance, something that persists today. Knowing this, slave traders attempted to dehumanize enslaved Africans by shaving their heads as they boarded ships. To reinforce a narrative of inherent inferiority, slave owners forced African women to cover their hair. White men and women intentionally framed the enslaved as subhuman to justify abuse and mistreatment and alleviate angst they may have felt due to those and other heinous acts. White men raped African women, resulting in children with features most often acknowledged as Eurocentric, namely straight hair and light skin.

The commonly differential treatment of these children, in addition to persistent societal affirmation of their physical traits, led to hierarchies that manifest as inter and intraracial colorism and texturism to this day. These manifestations contribute to institutional racism that impacts career opportunities and employment environments. Enter The CROWN Act (CROWN), introduced to Congress in 2019. Currently passed in seven states and the House of Representatives, CROWN awaits Senate approval. If approved, CROWN establishes legal standing against hair discrimination on a national level and presents language addressing gaps in the Civil Rights Act (CRA). The Supreme Court previously dismissed or ruled against cases of hair discrimination, arguing that the CRA defines race as unchangeable aspects of a person’s being. This definition doesn’t account for the innumerable hairstyles and textures innate to Black culture and most associated with the Black community; hence, why The CROWN Act is so necessary.

Between the buzz phrase “Representation Matters” and Covid-19 emboldening or requiring Black people to experiment with their hair, the prevalence and visibility of Black men and women proudly wearing their natural hair in a variety of settings is rising. Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott hit us with a major flex when he was recently sworn into office with the tightest ‘fro line-up I’ve ever seen. WFAA News 8 anchor Tashara Parker proudly wears her natural hair live, regularly challenging the status quo and in spite of community complaints and accusations of unprofessionalism. However, friends in TV production, telecommunications, cyber security, education, and other fields share stories about negative and bizarre reactions to their hair in the workplace, relationships, and random exchanges with strangers.

More than once I’ve been violated by co-workers stealing touches of my hair. Yet, we persist in taking up room and disrupting spaces by boldly wearing our hair as we please in the office, boardroom, classroom, newsroom, showroom…wherever there’s work to be done and fun to be had. To be present as our fully authentic selves demonstrates what it can look like to absolve our community of respectability politics and still flourish, thrive, and be successful; and it revokes the power of those who strive to uphold hegemonic ideology that frames Black bodies as subpar. In other words, they can have several seats and admire, from afar, our crowns in all their royal glory.